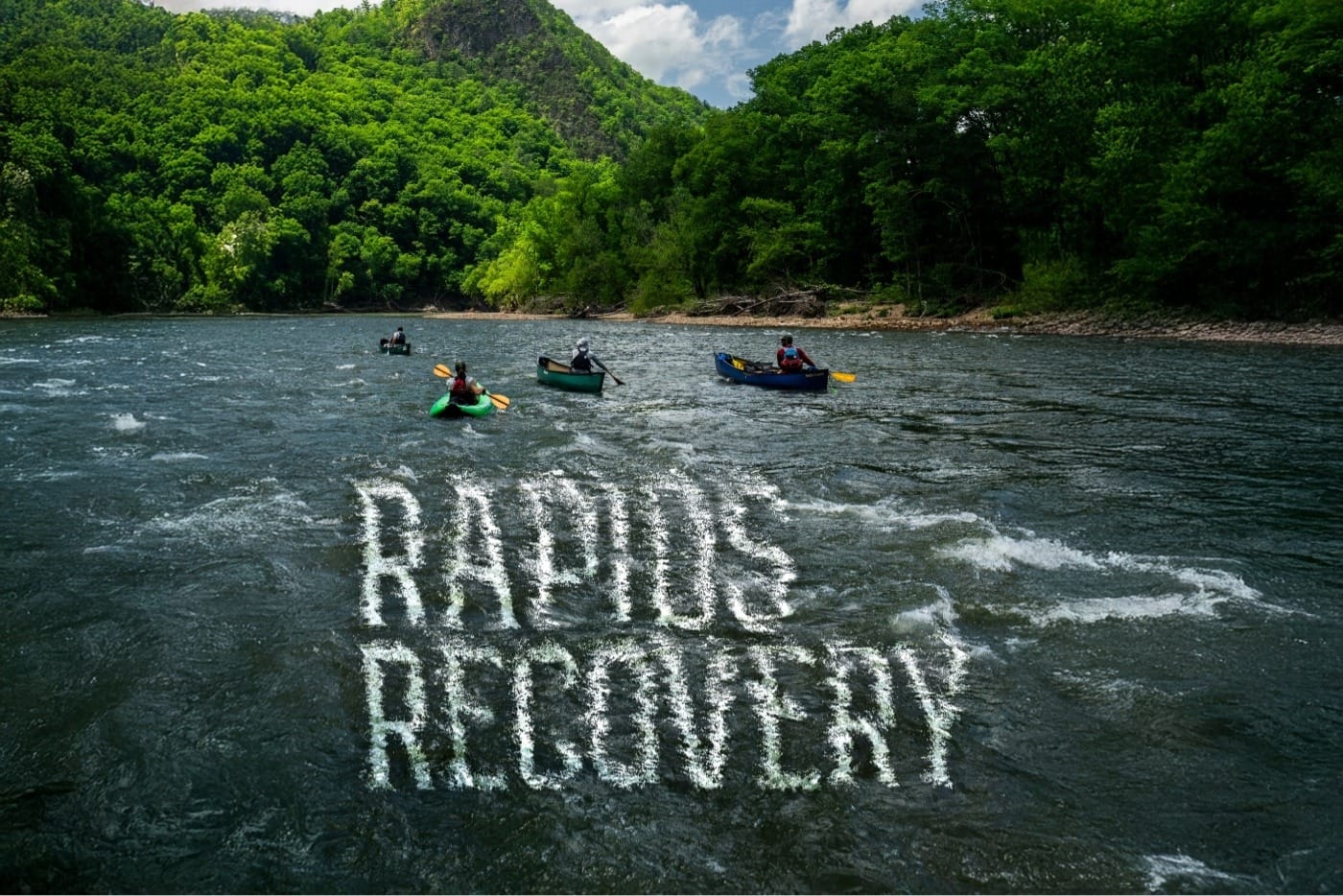

Hurricane Helene turned Western North Carolina's biggest river into a menace—yet a year later, it's clear that the French Broad is still the region's lifeblood. In Issue No. 1, our "Guide" explores this iconic Southern waterway and shows why it's still embraced by the communities that are rebuilding after suffering its wrath. See all the French Broad stories here, and be sure to get the full print issue in our shop.

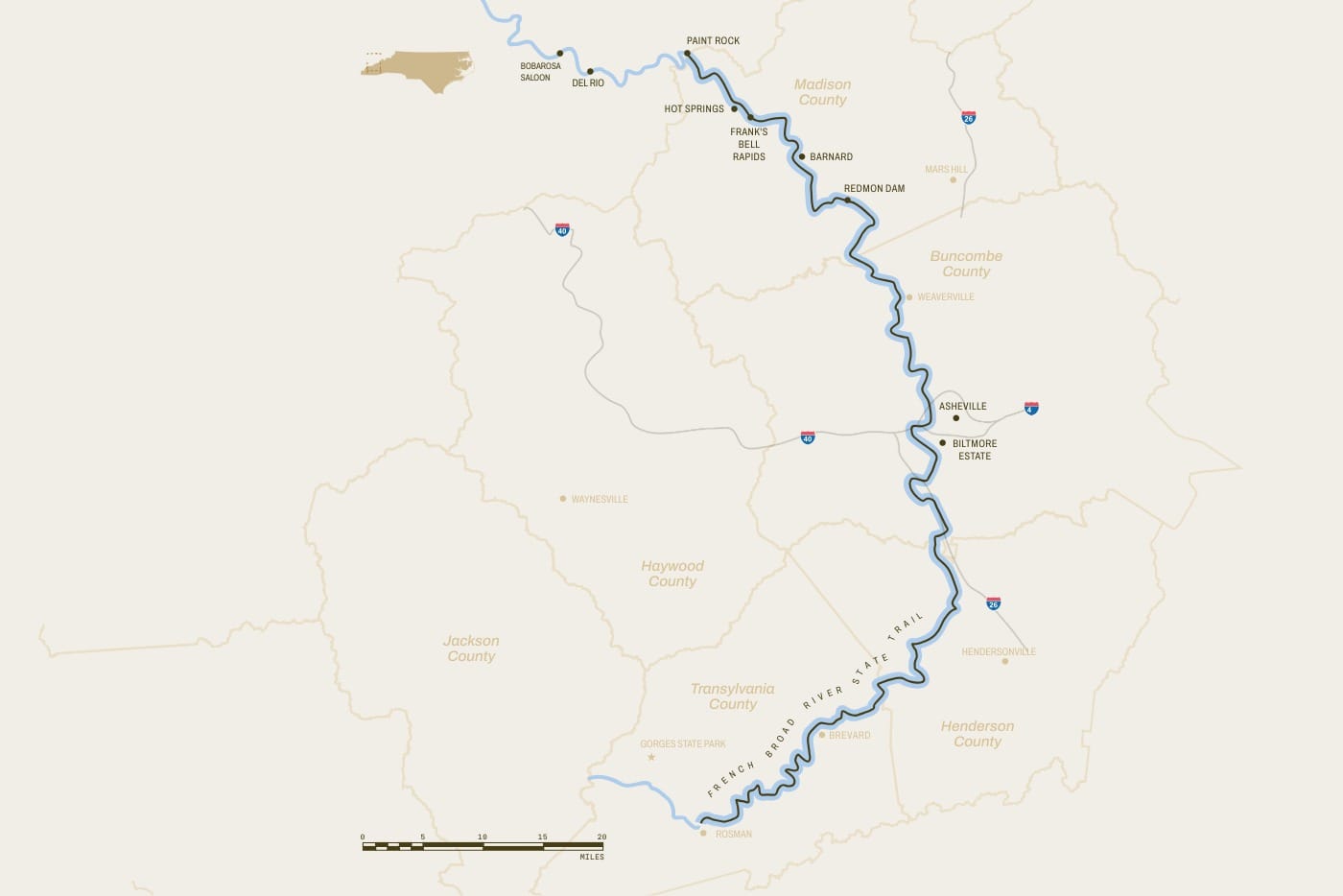

The French Broad River can feel like it runs in the wrong direction: it flows not south but north for 210 miles from its headwaters outside of Rosman, North Carolina, before joining the Tennessee River near Knoxville. A half dozen towns have sprouted along the French Broad’s corridor, leaning heavily on the river as a cultural and economic driver, first for farming, later for industry, and most recently for recreation.

Near the headwaters, there’s Brevard, a hub of mountain biking and rock climbing. Toward the middle, there’s Asheville, the region’s epicenter of culture. Further downstream are the small towns of Marshall and Hot Springs, two up-and-coming hamlets that have all the trappings of hip mountain towns—breweries and artisanal pizza—but still retain a rural, blue-collar vibe.

The French Broad River has served as an engine for the region for centuries, but when Hurricane Helene hit Western North Carolina on September 27, 2024, that same river turned into a force of destruction.

This spring, though, when I spent three days exploring the river, the trip was emotional in a way I didn’t expect.

The storm dropped more than twenty inches of rain in some places, all of which made its way into the French Broad. The river swelled to record-breaking levels, and flooded most of the towns that were built along its banks. The storm was devastating, taking hundreds of lives and causing billions in damage. I’ve lived in Asheville for more than twenty years and had never seen anything like Helene. You’ll still notice remnants of the storm as you travel along its corridor, especially in Asheville’s River Arts District, where the surging tide scraped the banks of its foliage and gutted many of the buildings that used to house restaurants and art studios. Further downstream, piles of timber and PVC pipes remain. Some islands have been stripped of their forest and turned into expansive sand bars.

But first the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the federal agency that oversees river infrastructure, and then a swarm of volunteers has, over several months, worked to remove debris and restore the banks. The nonprofit MountainTrue received a $10 million grant dedicated to the next phase of recovery. And the river itself is bouncing back. The whitewater rapids are unchanged; anglers are catching fish again; businesses in some of the hardest-hit communities are reopening. Guides are running trips, breweries are slinging beer, and chefs are cooking meals with locally grown ingredients.

“Hurricane Helene reminded us just how deeply our communities are connected to this river,” says Amy Allison, the director of North Carolina’s Outdoor Economy Office. “Outdoor recreation on our rivers and trails isn’t just a pastime—it’s a cornerstone of our identity and a powerful driver of local jobs and the region’s economic vitality.”

During the years that I’ve called Asheville home, I’ve paddled almost every stretch of the French Broad. I’ve canoed and camped through rolling farmland, tubed between breweries, rafted the burly whitewater sections and paddled and camped my way deep into the remote stretches of the river into Tennessee. This spring, though, when I spent three days exploring the river, the trip was emotional in a way I didn’t expect. I saw bald eagles soaring overhead and giant smallmouth bass cruising beneath our boats. I saw groups of middle schoolers testing themselves in whitewater canoes and old men fishing from the banks. I was overwhelmed by the resiliency of the landscape and the people who have staked their lives here. Considering the havoc that the French Broad wreaked, I wouldn’t blame people for fleeing the area altogether. But the communities on its banks aren’t turning their backs on the river. They’re embracing it all over again—and inviting others to come and do the same.

How to visit the French Broad Responsibly

Go Local

For much of the past year, people have been told to avoid Western North Carolina because of the damage. That was the right call in the immediate wake of the storm, but with the river’s recovery well underway, local business owners need visitors again. Local communities depend on the French Broad as a cornerstone of their economy. So come back—and, whenever possible, spend your dollars at local businesses: Eat at the pizza shop that was several feet under water last fall. Hire the local guides to steer you down the river or run shuttles so you can enjoy a seamless adventure. Drink local beer. Choose the local, boutique hotel over the corporate mega-chain—because that keeps more dollars in a community that needs it.

Leave No Trace

Leave No Trace is always an important principle, but even more so in a place where recovery is still underway. It’s common sense, really: Use established put-ins and take-outs. Camp in established campsites. Pack all of your trash out with you, whether you’re paddling for one day or ten. But there’s another layer you should consider: can you leave the river better than you found it? If you can safely remove some trash from the river, do it. If you have the time in your itinerary to volunteer for an afternoon of recovery efforts through MountainTrue, even better.

Dealing with Crowds

Before Helene, the sections of the French Broad near and within Asheville could feel like a zoo—hundreds of tubers and paddlers moving from park to park, bar to bar. As I write this, nobody is quite sure what the Asheville sections of the river will look like in months to come. They’re safe to paddle, but a lot of the access points managed as city parks are still closed. Many of the guide companies that operated trips in town before the storm aren’t sure if they’ll be able to provide the same service in the immediate future. But the throngs will come back, and my advice is to embrace it. Say hello to your fellow tubers and make some friends. Enjoy the tacos and local beers that you’ll find along the way.

Know, though, that there have always been stretches of rivers unvisited by the crowds. The first fifty miles of the French Broad are mellow and peaceful, passing through farms, and are used mostly by canoeists on multi-day adventures. The last fifty miles cruise through remote gorges far away from population zones, so if you have the capacity to get there, you might just have the river to yourself.

When to Visit

Though summer is the obvious answer, as the river offers a cool respite from the balmy Southern Appalachian days, don’t sleep on fall, when the green forests surrounding the French Broad turn shades of red, yellow, and orange. Most of the tourists stick to land during peak foliage season, but if you paddle a canoe and choose a mellow section of the French Broad, you’ll stay dry and have the river and all of those leaves to yourself.

Below, find some of Graham's favorite ways to experience the French Broad River, from mellow day cruises to overnight explorations.

Mellow Day Trip

Biltmore Estate & Asheville

7 miles, Class I

This post is for paying subscribers only

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.

This post is for paying subscribers only

Subscribe to get access to this and all premium content.