A version of this letter opens our inaugural print issue, which will begin shipping in early October. We're publishing it online to give you a sense of what we're up to. Intrigued? Get your copy of Issue No. 01 in our shop.

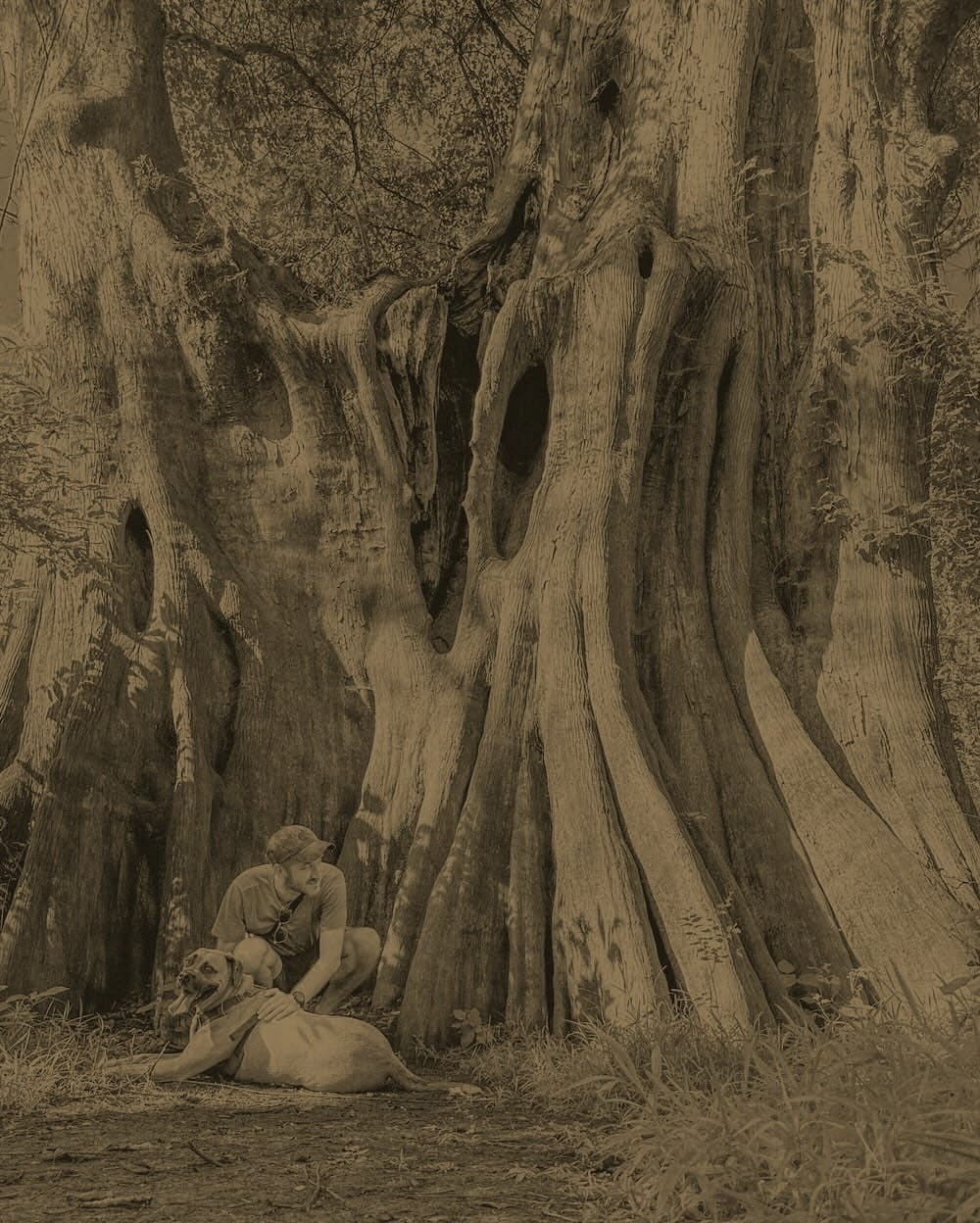

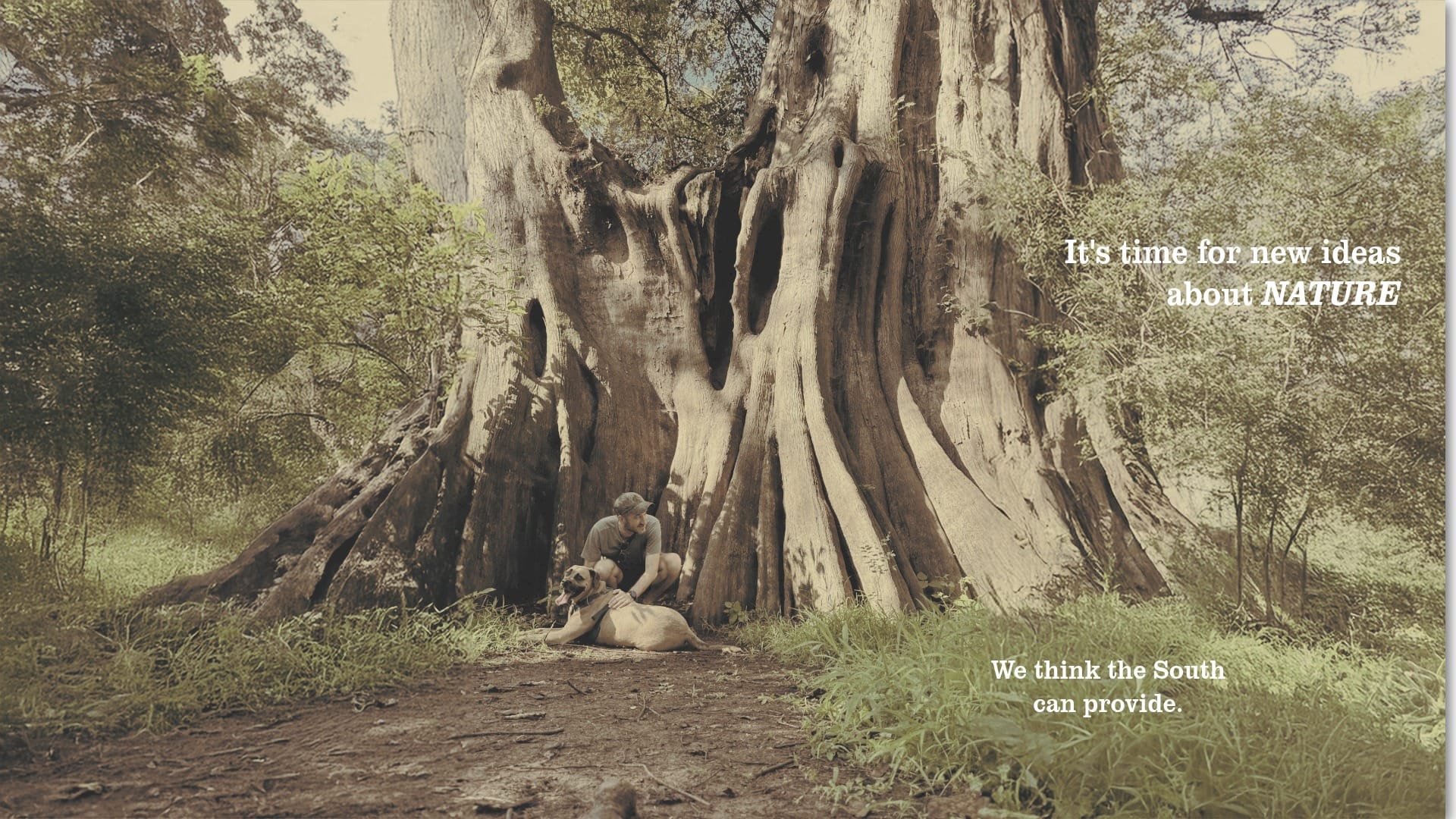

My wife and I have a ritual: at some point every spring or fall, we drive two hours north from New Orleans to the sleepy village of St. Francisville. We come, in part, to see the country’s largest bald cypress tree—which, according to some accounts, is the largest tree of any species east of the Sierras. It’s a hulking gargoyle of a being that has stood for a millennium, watching empires rise and fall.

As we rolled up the gravel road that leads to the tree last fall, I was listening to “Bar in Baton Rouge,” a song from country singer Lainey Wilson’s latest album. It’s about a heartbroken woman in a local bar who’s dreaming not just of her man but more inspiring environs. “I ain’t nowhere near the Rockies, or the Colorado sky,” she complains. For Lainey, sublime beauty seems to lie far outside her home state of Louisiana.

I guess she doesn’t know about the big tree, which grows just a half hour’s drive from the bars of Baton Rouge.

I’ve been up in those Western mountains, and I can’t deny their beauty. But our Southern mountains are far more ancient; they’ve been humbled by equally ancient rivers. The Southeast has lush grasslands, a sprawling mosaic of swamps, high-elevation heath balds—even thousands of miles of intricate underground landscape in the karst caves of the Cumberland Plateau. These places have been overlooked by outdoor media, though, which is why I created this magazine. I want you to fall in love, to find inspiration and new places to wander and explore. But I also want to challenge you, because we have work to do if we want to keep our Southern habitats beautiful and thriving and, importantly, accessible to everyone.

I want you to fall in love, to find inspiration and new places to wander and explore. But I also want to challenge you.

The print magazine is organized into four main sections; here, too, on this website you'll read four key kinds of stories over the coming months: first, “Field Notes,” short dispatches and mini-profiles of the creatures and landscapes in the region; next, a “Guide” to some wild locale, though we mean that loosely, including some first-person travel stories in that fold. The back of each print issue includes our “Parting Shots,” a literary-leaning collection of essays. At the core of this magazine are our features, which in our debut issue center around a question I had to consider as I launched this venture: What is the nature of the Southern thing?

That’s a reference to “The Southern Thing,” a song by the great Georgia band the Drive-By Truckers that explores the complexity of identity in this place we call “the South.” There are many Souths, of course, but given that the region was slow to industrialize, the interplay between people and landscape is key to almost all of them.

Beginning in early October, and continuing for the next six months, we'll be publishing the stories from our debut issue here on this website. Some stories will be free for everyone; most will be behind a paywall, for the subscribers who have helped this magazine happen. (We hope you'll become one!) The line-up includes a story by New York Times-bestselling author Kim Cross, who considers how hunting and fishing traditions helped turn her Japanese family into a certain kind of Southern. For my own contribution, I examine what it means that the Delta—a region often known as the world’s “most Southern”—is hard to regard as stereotypically “wild.”

But the old idea of wilderness, it turns out, was mostly a fantasy. For as long as our species has been alive, humans have always been a part of it… We need new ideas about nature.

There are many Souths, of course, but given that the region was slow to industrialize, the interplay between people and landscape is key to almost all of them.

Perhaps those can be found here, too. Or if not new ideas, then old ways that should be better known. I’m currently reading a book called Southern Folk Medicine, by Phyllis Light, and I’m struck by her observation that ours is the only region to develop a localized tradition of folk medicine—a mingling of Indigenous and settler ways of knowing the landscape intimately. The story that inspired Steven Gray's cover photo is about how that same mingling has helped ensure people here never stopped lighting their forests on fire.

This magazine aims to do the same. Welcome to Southlands.