This story originally appeared in Issue No. 01 of Southlands. You can escape your screen and dive into a print version of the story by ordering a copy in our shop. And be sure to subscribe to receive the next two issues.

Early each summer, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries sets up a lottery for the state’s wildlife management areas, selling three alligator tags to each hunter that gets drawn; the number of hunters is determined by assessments of the alligator population in each area.

LDWF publishes success rates from previous seasons, so on a whim a couple of years back, I applied (and was drawn!) for a WMA that had good odds: Pass-a-Loutre. It’s as south as you can get in Louisiana—the very tiptoe of the Boot—and it’s not easy to get to, but I found a crew willing to try. Dave, a local wildlife biologist, had also drawn tags for Pass-a-Loutre, and our buddy Logan had access to a boat that could get us across the Mississippi River, into the heart of the WMA.

Day 1: Setting the Lines

We drove down to Venice, Louisiana, on a Sunday morning and waited for the weather to clear up before hitting the water. On these lottery hunts, you’re required to use a hook and line to bait the gator—as opposed to dragging a large treble hook through the water or shooting them out in the open—so we scouted canals for places to set our bait. At each spot, we planted a sixteen-foot bamboo pole, then tied a heavy line to the base and used a clothespin to suspend the line and hook about six inches above the water. Traditionally, hunters use rotting chicken as bait, but this team was far from traditional: we used a mix of fresh pigeon, roadkill nutria, and a mullet that jumped into the boat while we were scouting. With our lines set, we headed out into the Gulf and fished until sundown.

Day 2: Harvest

We returned the next morning to check the lines. You’re allowed to set two per tag; Dave and I each had three tags, so we set twelve in total.

The first couple of hooks were untouched. The next was missing the bait, but otherwise undisturbed. We found a line that was pulled down, but the hook had been shaken out several yards away. So far, no luck.

Then we pulled up to the line that had been set with the mullet. Bingo. The seven-foot gator that was attached was on shore less than ten yards away, so I used a .22 rifle to kill it quickly and, with my heart racing, climbed out of the boat to retrieve it. I later learned that alligators will prey on each other, so smaller alligators (yes, seven feet is still fairly small) often retreat to the shoreline when snagged or injured.

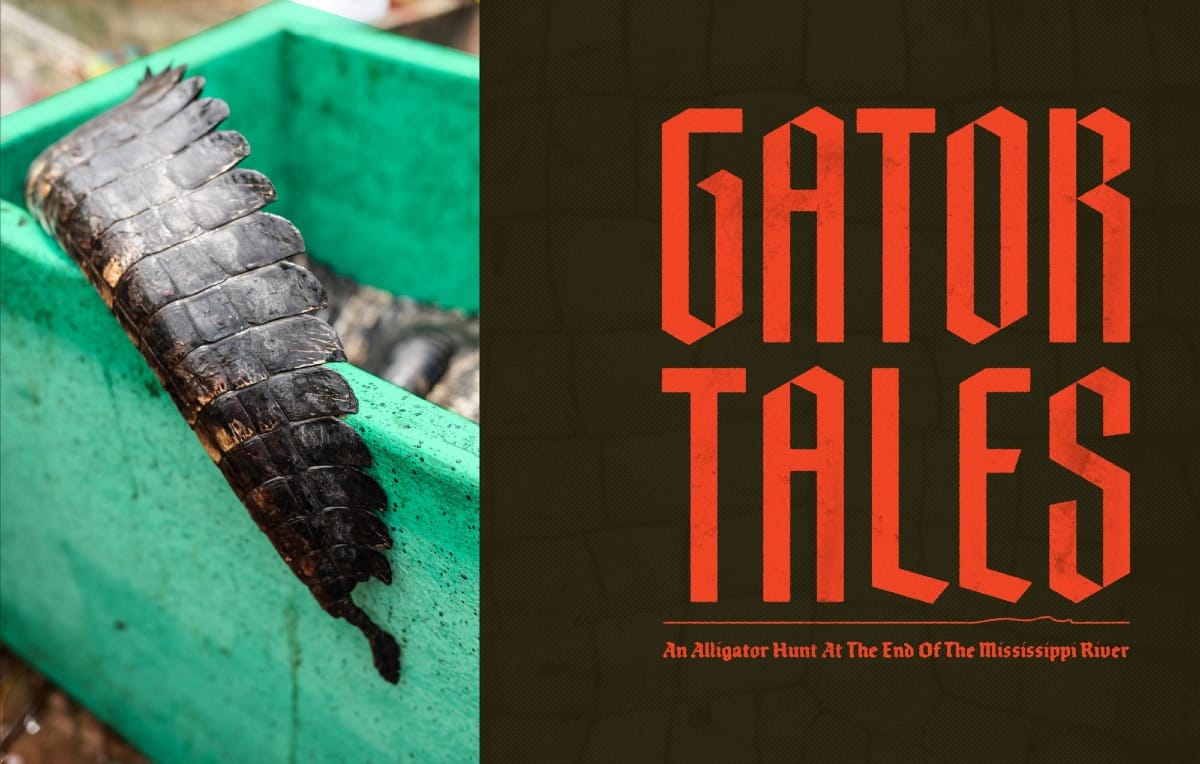

The next few lines were duds, but eventually we made our way back to one we had baited with some of the nutria and found an even bigger gator on the end, clinging to the bottom under a few feet of water. It was Dave’s turn to harvest, so I pulled the line in slowly until the gator’s head surfaced and he could get a clean shot to the small, quarter-sized target area just behind the eyes. We loaded the carcass into the boat and tagged the tail. Dave posed with the gator across his shoulders.

We ended up with one more small gator that morning, filling three of the six tags.

After the Harvest

Turns out that alligators are a lot of work to clean, but we tackled it as a team and had all three butchered within a few hours. We preserved the hides from each so that they could be tanned and eventually used for leather, and we saved as much meat as we could, removing every trace of the fishy fat lines. As with many wild game meats, fresh gator can have a reputation for musky flavor, but these fillets simply smelled like salt water brine, with the color of fresh pork.

I cooked a sauce piquante with a couple of fresh fillets, then froze the rest for later use—some earmarked for fried gator bites, the rest packaged for stews and to share with friends. One of the things I like most about hunting is learning how to work with wild game meat, learning the nuances of each type, and alligator certainly has a lot of nuance. I ended up winging a couvillion at a large gathering of friends, cooking the alligator in a wild game broth until tender, then mixing in fresh fish from the Gulf. The crowd raved about it.

Dave and I still had three tags to fill, and with a month left in the season we had hoped to get back down to the WMA, but we couldn’t put a plan together. Hunters who are drawn for the lottery don’t have to fill all of their tags, but I’m told that LDWF prefers that we do, and may even offer preference in future lotteries to hunters who’ve shown success in the past. And that seems fair, given the state’s goals in managing the population.

One thing I hadn’t realized when I put my name in for this: alligator hunting is a lot of work, almost all of it dirty work. Hunting in the South can be grimy—lots of blood, sweat, and DEET—but this hunt was more intense than anything I had previously experienced. There are people who make this their livelihood, and can even make it look easy on those swampy reality TV shows, but it’s a tough way to fill a freezer, let alone make a buck.

It sure does make for some really rich stories, though.

This story appeared in Issue No. 1 of Southlands (and, before that, in James's newsletter, The Boil Advisory.)

Alligator Sauce Piquante

Ingredients

This post is for paying subscribers only

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.

This post is for paying subscribers only

Subscribe to get access to this and all premium content.