As we put together our second issue of the magazine, built around the theme of PUBLIC/PRIVATE, we are running a series of "spotlights" focused on Southern public lands. And this month, which marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the U.S. Forest Services "roadless rule"—which is now under threat—we thought one of the region's largest blocks of public land was a suitable subject.

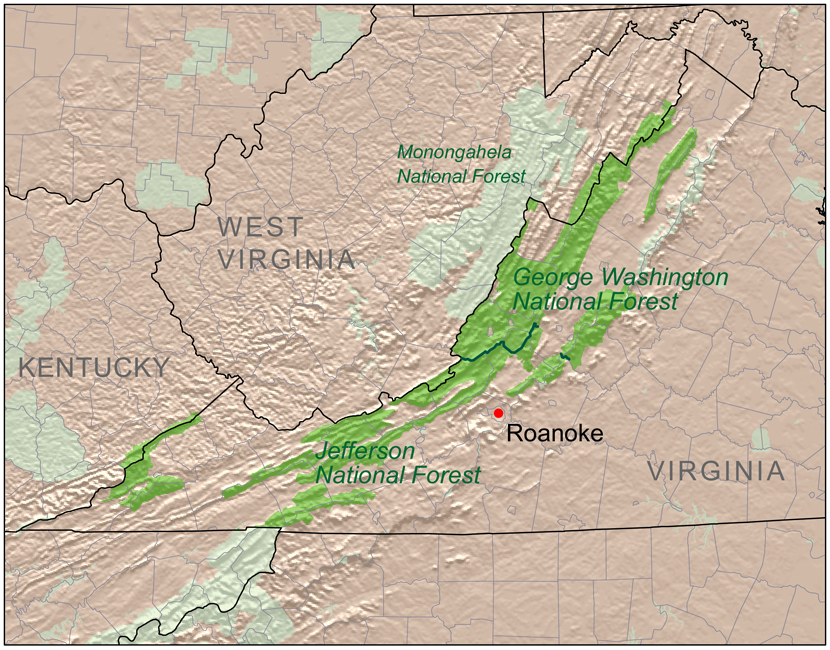

History: Assembled piecemeal in the early twentieth century, often from degraded land. Dozens of separate purchases gradually consolidated into two forests—later administratively joined—that stretch along the spine of Virginia and into West Virginia and Kentucky.

Geology: Ridges and valleys reflect folded and faulted rock—sandstone, shale, and limestone—in some of the planet's oldest mountains. Elevation ranges from roughly 1,000 feet in river valleys to over 4,800 feet on peaks like Mount Rogers, creating sharp climatic and ecological gradients.

Ecology: A stronghold of Appalachian biodiversity: oak–hickory forests on ridges, spruce–fir forests on peaks, mixed mesophytic cove forests, rare mountain bogs. Hundreds of tree species and one of the highest diversities of salamanders in the world. Cold, high-quality headwater streams provide habitat for native brook trout and imperiled freshwater mussels downstream.

How people use it: Hiking, hunting, fishing, and dispersed camping. Long-distance trails—including large sections of the Appalachian Trail—draw visitors from far beyond the region. Scenic byways like Skyline Drive’s southern reaches and mountain roads to places like Reddish Knob are popular, while backcountry areas offer some of the quietest, most intact landscapes left in the southern mountains.

Reddish Knob is, at 4,400 feet, one of the tallest peaks in Virginia. Drive to the top and you look down on a panorama of wildness: an expanse of forests that are uncrossed by any road.

It's a rare thing in the South. Indeed, by the dawn of the twentieth century, it had become clear that the eastern United States faced a public land crisis: almost everything was privately owned, which made it hard to protect crucial landscapes. Scientists had grown particular worried about mountaintop forests, which protected delicate headwaters—and therefore served everyone downstream who depended on clean water.

The Weeks Act, passed in 1911, allowed the federal government to buy up private land to assemble new national forests. Reddish Knob sat within one of the first of the new forests. Now known as George Washington National Forests, before its purchase some portions had been reduced to "weather-white ghosts of trees [that] stood on the desolate slopes." The creeks were often poisoned by tanneries and dye plants. Now, though, the forest has returned. Combined with the adjacent Jefferson National Forest, it constitutes one of the largest tracts of public land in the east, one that contains huge tracts of legally designated wilderness.

Just because land is federal property doesn't constitute full protection. National forests are working forests, frequently logged—and the logging companies carve roads that crisscross the forest. Those roads can be considered "a multiplier for forest destruction," fragmenting habitat and inviting in invasive species. The Wilderness Society has found that forests containing roads are four times likelier to catch fire.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton made the drive up Reddish Knob to announce his intentions to create what became known as the "roadless rule": no new roads in areas where the roads did not already reach. This Virginia mountaintop was a fitting site, since the state holds some 330,000 roadless acres, including nearly a quarter of George Washington National Forest; local advocates had been working on preserving roadless areas for years already. And, while Clinton's idea was hugely popular, with 95% of the 1.6 million public comments expressing support, the enthusiasm was even higher in Southern Appalachia. (Here, according to our friends at the Southern Environmental Law Center, the public support reached 97%.)

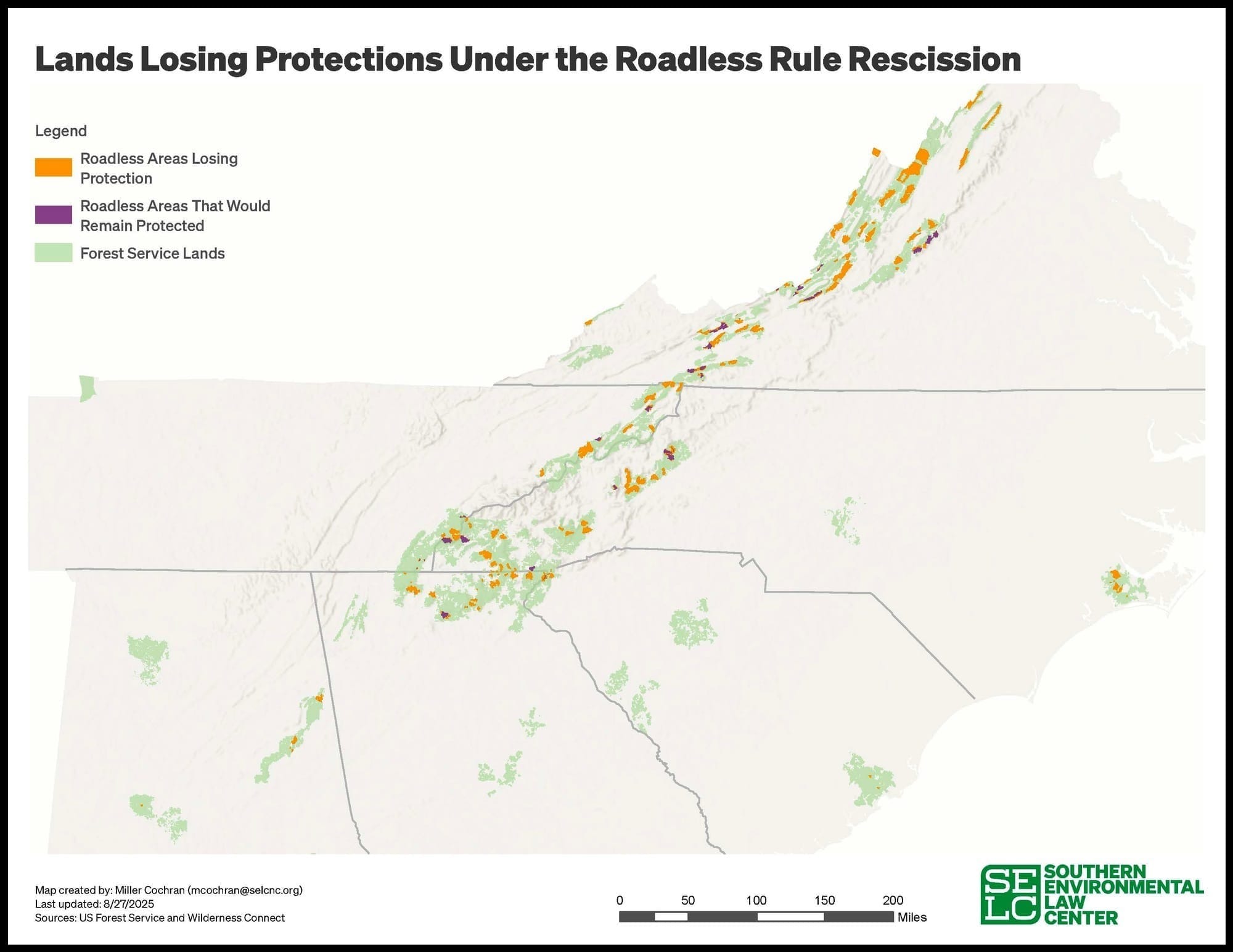

Two years after Clinton's Virginia mountaintop announcement, the roadless rule became official. This month marks its twenty-fifth anniversary. Unfortunately, now the rule is under threat: the Trump Administration has announced its intention to revoke its protections. (Their rationale is that roads make it easier to fight wildfires. But, unsurprisingly, many experts suggest that rescinding the rule will actually lead to more fires.)

The Southern Environmental Law Center—who, disclosure, have bought ad spaces in the magazine's first two issues, but did not ask me to write any of this—has launched a campaign to fight for the roadless rule. Some of the most beloved forests in the South have been well-served by the roadless rule for a quarter century. And here, where wild public land is so rare, it would be a shame to lose even an inch.