This story originally appeared in Issue No. 01 of Southlands. You can escape your screen and dive into a print version of the story by ordering a copy in our shop. And be sure to subscribe to receive the next two issues.

Wendy Cowan was half a mile from her mother’s house, photographing a frog in a mud puddle when the bear arrived. All morning, her mom’s dog Ripley, a willful German Shepherd who Wendy calls her soulmate, had been running after squirrels and then boomeranging back to her side. But this time, when the dog sprinted down the forest road, a 350-pound bear loped alongside her. “They were chasing each other,” Wendy recalled later. “It looked like they were playing.”

That fall, Wendy’s work as an art conservator had been stressful. A project had fallen behind, and she’d been worried about how she’d catch up. The woods were her happy place, familiar territory where she could let her anxiety go. The threat of ticks, chiggers, and poison ivy, which thrive throughout Virginia summers, had kept her away for months. Now that it was fall, the weather had cooled, and she finally felt safe to return to the woods near the property where her family has lived for six generations. In all that time, as far as she knew, no one had been threatened by a bear.

Wendy camped and hiked often. She knew from ranger talks that if a black bear approached her, she should stand her ground and shout until it left. Ripley was another story. Smart but unpredictable, the dog’s enthusiasm for a chase unnerved her. As the animals neared, Wendy screamed at the bear to back off and called Ripley over. They’d had a great morning together. Ripley had swum in the creek, and later they’d traipsed through a tobacco field laced with morning glory. “Ripley!” she shouted again. “Come here.”

But the animals ignored her and kept running, one in pursuit of the other. As they passed, the bear turned its head and its teeth tore through Wendy’s thigh, ripping the new leggings she was wearing that day. Blood beaded through the tear in the ruined pants. Instead of registering pain, Wendy felt annoyed. She figured she’d have to see a doctor, but she’d already promised to take her elderly mother to see a dermatologist that afternoon.

Wendy spread her arms and legs out like a starfish, doing her best to make her petite body appear bigger than it was. Ripley was gone, but the bear stopped and faced her. She yelled again, and the bear rose onto its haunches and lifted its own arms, mirroring her. For a moment, they were the same height, face to face and swaying like a dancing couple. Then the bear yawned, and Wendy knew she was in trouble.

A century ago, North America’s black bears were in dire straits. Deforestation, overhunting, and food loss pushed the animal into stark decline. The population, whose range stretches from northern Mexico through nearly all of the United States and Canada, dwindled from an estimated peak of 2 million animals to a mere two hundred thousand.

As their habitat fragmented, the remaining bears were pushed to remote woodlands, becoming so hard to find that on a hunt in Mississippi in 1902, Teddy Roosevelt decided to spare the emaciated bruin his guide located for him to shoot. The story of his mercy inspired the Teddy Bear, transforming a fearsome beast into a beloved, friendly, storybook friend.

The bear became a complicated symbol. You had on the one hand the storybook friend of the Teddy bear; on the other, there was William Faulkner’s famed 1942 story “The Bear,” about a boy obsessively pursuing a “tremendous bear with one trap-ruined foot.” Immune to bullets, the animal haunts generations, “towering” in the boy’s dreams even before the child ventures into “the unaxed woods.” The animal is totemic, “an anachronism,” Faulkner writes from “an old dead time,” as much a primal memory as it is a living remnant of America’s ravaged wilderness.

Now, more than eighty years after the publication of Faulkner’s story, what the black bear means is changing again. Reforestation, public land restoration, and a highly regulated hunting season have rehabilitated populations. Well over half a million now live in North America, thriving in over forty states. Both Louisiana and Florida black bears, subspecies recently considered endangered, have recovered. Last year, after a 37-year respite, Louisiana opened its bear season to eleven hunters. Florida plans to reopen its season this fall, making 187 hunting tags available. These bear hunts have been met with both enthusiasm and protest. No longer limited to outlying wilderness, black bears increasingly share space with humans, gorging at suburban compost bins, peering through living room windows, lumbering down city streets, and even swimming in backyard pools.

In Virginia, where Wendy lives, the Department of Wildlife Resources has monitored bear activities since the 1950s, and the population, which dipped to roughly one thousand, is now flourishing at around eighteen thousand animals and growing. These days, rifles, muzzleloaders, crossbows and certain kinds of handguns are permitted in the state’s annual hunt, though rules vary by county. When it comes to taste, bear meat is unpredictable, running from gamey to sweet or even rank, depending on what the bear’s been eating; so, like most carnivores and omnivores, the animals aren’t usually hunted for food. Instead, bears are trophy animals, killed for sport and usually taxidermied afterwards for display. In Virginia, the season lasts from October to January, and hunters kill around three thousand bears annually, about one sixth of the state’s population.

“This was not the day to mess with her,” Martin said. “There’s no one to blame in this.”

“Getting to see a bear is like that true wild experience,” the Virginia state deer, bear and turkey biologist Katie Martin told me, before lamenting that most people don’t know how to behave around them. Whatever ursine rules of conduct were once shared amongst neighbors have been replaced by memes and social media messaging rarely based in fact. Some people have “fears from movies about what a bear might do,” Martin said. Others “think of them as cute and cuddly.” While extremely rare, black bear encounters usually occur when an animal is startled at close range, chased by an off-leash dog, or lured by human food. At national and state parks, tourists have been known to hand-feed bears, an activity banned by law because of how it habituates the bears to humans, putting everyone in danger. Some people coax black bears into selfies. In a viral video filmed in North Carolina, a group plucks three cubs from a tree and exclaims how adorable they are. None of the humans got injured that day, but one cub ended up in an animal rehabilitation facility where it was permanently separated from its mother. As Martin puts it, bears draw out “the best and the worst in people.”

When unnerved, a bear will woof, salivate, click, growl—or yawn, in the case of Wendy’s bear. Seeing that signal, she picked up a stick to defend herself, but the wood was rotten and fell apart in her hand. Then she looked for a tree to climb—black bears excel at climbing, but she figured she could kick it from above if it followed her. Only, the pines around her were old and had long ago shed their lowest branches.

When the bear slashed her back, she had nothing to defend herself and nowhere to hide. But instead of registering pain, her body flooded with a deep sense of calm, a shock response likely combining a mammalian pain suppression response called stress-induced analgesia and altered perception known as peritraumatic dissociation. Leaves hovered midair. Time stretched and bowed. When she pushed it away, the bear’s fur felt as thick and soft as Ripley’s. The bear vanished, chasing the dog, and Wendy ran toward a newly harvested cornfield. If the tractor was still there, she might be able to shimmy beneath it.

Wendy didn’t even make it halfway when the bear returned and clamped its teeth into her neck. She fell to her knees. Her hair was heavy. She tried to crawl toward a fallen fence, hoping to hide in the space beneath the planks, but she found she could no longer move her arms or lift her head. Her body was curled, her hair tangled in barbed wire. The sky was cloudy and sunny at the same time, light slipping between the branches. Then it was back: illuminated, towering, and furious. Wendy could see the mammary glands on its chest were swollen as if it had recently nursed a cub.

The thought came unbidden. This could be over. She didn’t have to fight. She could die. She wasn’t even scared.

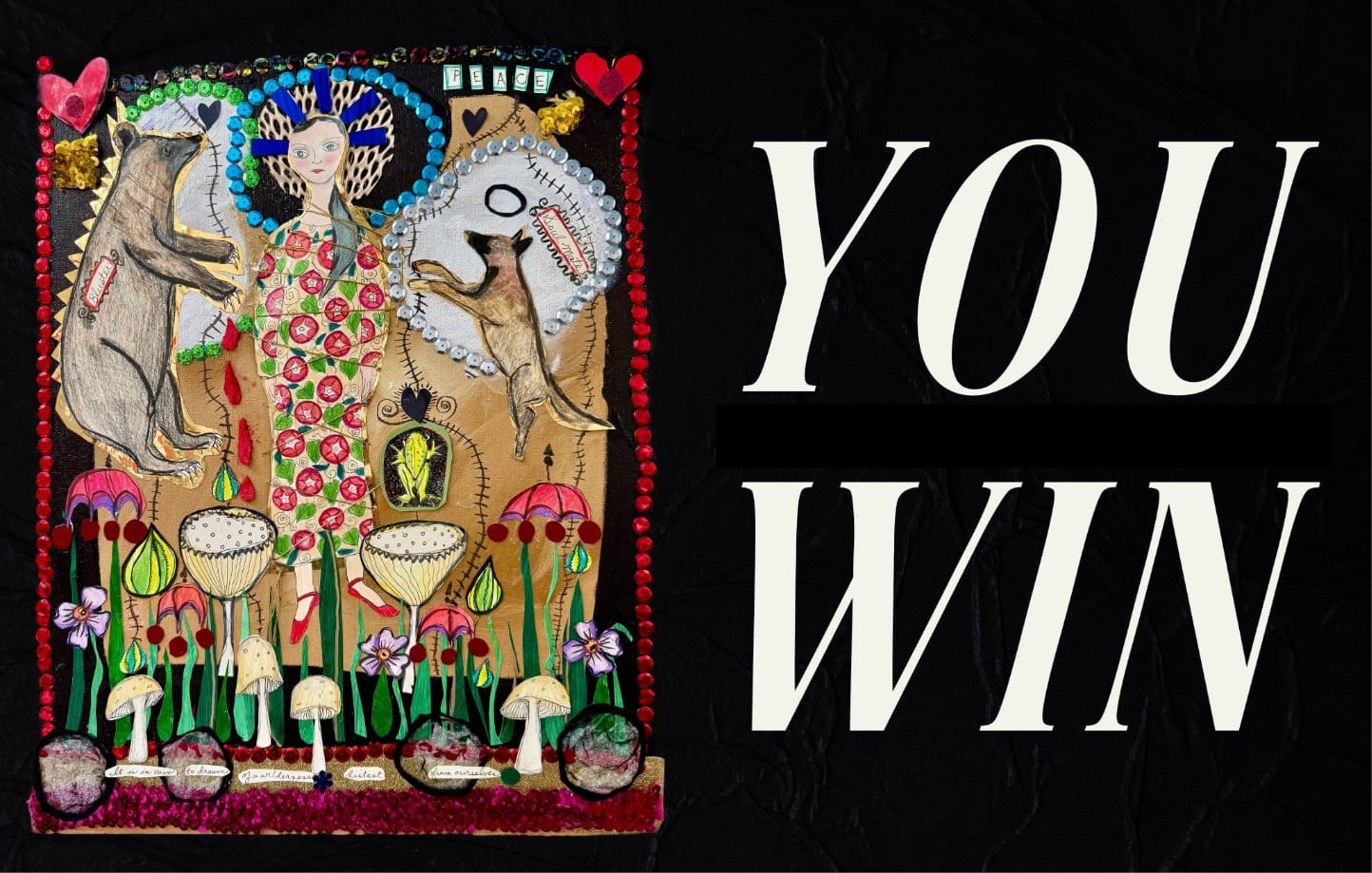

“You win,” she whispered. “You win.”

By the time the bear left, Wendy was exhausted and broken, bleeding just about everywhere. She and the bear had jousted on and off for twenty minutes, making their way down a quarter-mile stretch of road. Her phone was gone, flown out of her pocket during the tussle, but she managed to locate it and stumble to the cornfield, where, despite terrible reception, she got a call through to her mom’s 86-year-old neighbor, a DMV employee named Connie Perkins who happened to be off work that day. “Are you looking for Ripley?” Connie asked when she answered the phone. “She’s at my place.”

Lying down in the cornfield, Wendy was incredulous. Ripley brought her the bear, but it occurred to her now that Ripley had also coaxed it away. As the dog ran towards Connie’s house, it had taken longer for the bear to run back and forth between them, which had bought Wendy time. Ripley likely saved her life.

“I’ll be right over,” Connie said, when Wendy filled her in on what’d happened. “I’m on my way.”

Home to just twelve thousand people, Lunenburg County is mostly forests and farms. Yet, in the time it took for the helicopter to land for an emergency medevac, word spread about the attack. Some folks heard about it on police scanners. Others received phone calls from neighbors. Around fifty people came to watch Wendy’s rescue, though she remembers little of it. By then her brain had switched from hypervigilant to barely aware.

She had 56 puncture wounds on her back and face, bites in her shoulder, thigh, and neck, and possible organ failure. Her cervical spine and scapula were fractured and her rotator cuff was torn. Her skull was visible through the claw mark on the back of her head where she’d been scalped.

When I asked why Wendy’s attack was so ferocious, Martin told me that, like humans, bears have unique personalities. Wendy’s bear was fifteen or sixteen, which makes it late middleaged, and it had a cub to care for. Her caloric needs were growing as she prepared to den down for winter, but her food supply had diminished. The cornfield where she’d likely eaten all summer had vanished overnight, the ears harvested and sent off. The bear was famished. “This was not the day to mess with her,” Martin said. “There’s no one to blame in this.”

Yet, blame abounds. Wendy’s been chastised on social media for letting Ripley walk off leash, for going into the woods without bear spray, for hiking without a gun. The bear was blamed, too. The attack prompted “an outcry among hunters,” Martin told me, to “go get all these bears,” a reaction that would’ve violated hunting laws and potentially threatened the rehabilitated population.

“If she wanted to kill me, she would have killed me,” Wendy muses often. At 59 years old, she’s joyful, athletic, and full of curiosity about the attack. Nearly everything about the incident was an aberration. Unlike most apex predators, black bears are timid animals, more apt to run away or climb a tree than approach a human. Those woofs and clicks are yawns that signal unease are the ursine equivalent of “using their words.” Such behaviors, called bluster, are meant to scare off trouble, not amplify it. If they happen at all, assaults are brief—swats or smacks followed by a swift retreat. Persistent violence is almost unheard of.

Wendy didn’t believe her attacker deserved to die, but it wasn’t her choice. “Based on the magnitude of the injuries,” Martin told me, “it was not feasible for us to leave a bear like that on the landscape.” Hunting season would soon open and more people would be in the woods with their dogs. The likelihood of another incident with that same bear was too high. Martin made the call, trapping the animal in a giant cage, checking its DNA against the DNA found on Wendy’s clothes, and euthanizing the animal herself. Her actions, she hoped, would signal to the community that wildlife management was on top of the situation and, perhaps more importantly, that a bear-hunting spree was unnecessary.

“Can you see the scar?” Wendy asks me from across the metal work table in her studio in Richmond’s East End. Her straight gray hair stretches in a ponytail down her back. When she touches her face, I spot the faint indentation that slips down her forehead and picks up again along her cheek. The plastic surgeons tidied her wounds so expertly that they’re hard to make out. “The bear stopped at my eye, thank goodness,” she says. She points out another faint line, this one running across her neck.

She takes out her phone and tilts it so I can see. On the screen are photos from her medical record, taken not long after her arrival at the hospital. Her back looks like a Jackson Pollock mock-up: pink calligraphic etchings from the bear’s curved claws contrast with the deep, red gouges of the bite marks. The wounds stretch from shoulder to tailbone and wrap around her torso. It’s hard to reconcile the damaged body on the screen with the smiling woman before me.

There’s a small coffee shop in the back of the building. As we walk there, Wendy says hello to one person after another. Everyone knows her here, which means they know about the bear. Since she already has the photos pulled up on her phone, she offers to show them to anyone who’s interested.

A painter stops to look. The two of them have bonded over their experiences with psychopharmaceuticals. He treats depression with mushrooms. At the hospital, Wendy took ketamine to manage pain. Her nurse turned into Kurt Cobain, and the room melted like a Dali painting. The barista asks to see the photos, then tells us how she was badly burned as a child, that her recovery had been hard, too. Connections like these happen often to Wendy. Since the bear attacked her, she’s found allies everywhere, reuniting with old friends, befriending strangers, bonding with hospital staff. “I see this as a gift from this bear,” Wendy says about her expanding sense of community. “Sharing the story … keeps me alive.”

“You think you’re dying,” Samantha said, “and you’re noticing how beautiful this animal looks to you. Isn’t that something?”

During her month-long hospital stay, she underwent two neck surgeries and numerous procedures to tidy up the scarring on her face. Her head was stapled closed, but for weeks her scratch and bite wounds had to remain open so that they could heal from the bottom without forming abscesses. Every few days, a team of nurses would pull the packing from her wounds—some were an inch or more deep—clean them, and repack them. The nearly two-hour process was excruciating and Wendy spent a lot of that time talking with her care team, trying to distract herself. One nurse used to sing Outkast songs while he worked. Another nurse, who came from South Sudan, shared recipes for West African Peanut Soup. “They added some laughter and lightheartedness,” Wendy said, noting that their support helped her keep her spirits up, enabling her to stay positive through what turned out to be a grueling recovery.

Weeks in bed caused Wendy’s muscles to atrophy. Occupational therapists and physical therapists had to help her regain mobility and perform basic tasks that had become difficult. She lost thirty pounds. Her trauma surgeon tried to get her to drink protein shakes—teasing her that she would make it to the base camp of Mount Everest the next year—but she couldn’t stand the taste. “I might be at base camp,” she’d joke with him, “but I am never going to be able to drink an entire protein shake.”

The only time Wendy got really upset, said her friend Samantha Masone, was when she talked about hiking. She wasn’t sure she’d ever feel comfortable in the woods again. Her best friend since eighth grade, Samantha had bought Wendy replacement leggings after the bear ripped apart her original pair. Now, she offered to lead Wendy through a session of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy, or EMDR, part of her practice as a trained trauma recovery counselor. Wendy accepted. While recounting the assault, she clicked small buzzers that she held in each hand. The sound and movement stimulated both sides of her brain, creating new neural networks that moved the traumatic memory from the limbic system into an area of the brain that helped her put words to her experience.

Toward the end of the session, Wendy told Samantha about the moment that was nearly her last—the sky cloudy and sunny at the same time, the bear’s dark fur tinged with gold from the late morning sun, an expanding sense of peace as she surrendered. “You think you’re dying,” Samantha said, “and you’re noticing how beautiful this animal looks to you. Isn’t that something?”

Though she tells it expertly now, Wendy’s careful with her story, declining to speak much with the media lest they sensationalize the assault and incentivize hunters to exterminate more bears. She’s acutely aware that, in the wrong hands, her experience could spark something terrible, a human-on-bear rampage, a wild ferocity.

The boy in Faulkner’s story “The Bear” has a similar transformation, changing from a hunter to a protector. After four years of pursuit, they finally meet in the woods and make eye contact, “synchronized to the instant by something more than the blood that moved the flesh and bones which bore them.” Death is proximate. The boy holds a gun. The bear leers over him. Time stalls. In Faulkner’s story, the boy is merciful. He chooses not to shoot. During Wendy’s assault, the roles were reversed. Wendy said, “You win,” and the bear shuffled off.

Nine months after the attack, the state bear biologist Katie Martin called Wendy with an unusual idea. By then, Wendy was back at work and more or less living her life. Every summer, Martin explained, the Virginia Wildlife Department tags bears, trapping them and putting them to sleep so they can attach trackers to monitor their movements. “Do you think you might like to have a different kind of bear encounter?” Martin asked. “You could be very close to another bear in a controlled setting.”

To be wild is to be uncivilized. Uncultivated. Unpredictable. A wild thing is passionate, strong-willed, maybe even crazy. But Google the word and those definitions fold back on themselves.

Samantha says that most people who’ve experienced a devastating animal attack aren’t like Wendy. They associate shame with the event and fixate on the possibility that if they’d just done one thing differently, the assault might not have happened. Wendy is different, intrigued by the animal that nearly took her life and deeply invested in the species’ wellbeing. She jumped at the invitation to tag bears. So far the traps have been empty on the days Wendy’s joined Martin, but she’s determined to keep trying. “I’m not that strong of a person,” she told me. “This has made me stronger.”

Booming bear populations signal that this country has made real progress in protecting our landscapes. Poised at the top of the food chain, apex predators like bears are so hyper-sensitive to environmental change that their presence is considered a reliable indicator of environmental health. Yet more bears also means a higher likelihood of bear attacks,like Wendy’s. While I was writing this story, a black bear killed a man and dog in Collier County, Florida—a first for the Sunshine State. Days later, the state responded by killing three local bears, an excess made me wonder if their end goal had shifted from safety to revenge.

To be wild is to be uncivilized. Uncultivated. Unpredictable. A wild thing is passionate, strong-willed, maybe even crazy. But Google the word and those definitions fold back on themselves. In the forest of URLs is a litany of human invention: wild-scented deodorants, a memoir of a self-seeking trek in the woods, various sports teams, objectified girls. The word wild now markets human ferocity, bad behavior, and an ephemeral longing. “It is in vain to dream of a wildness distant from ourselves,” Thoreau wrote back in 1856. “There is none such. It is the bog in our brain and bowels, the primitive vigor of Nature in us.” Two hundred years ago, he could already see what Wendy was forced to face. Wildness isn’t our opposite. It animates us, even when it threatens our lives.

These days, instead of protecting ourselves from a violent and unpredictable wilderness as our ancestors did, we’re more likely to personify wild places as if they were badly wounded patients, dependent on us for survival. Perversely, we situate ourselves as saviors, the only ones capable of helping what we actively destroy. Portrayed this way, it’s no wonder that tourists take selfies with cubs or that the public is caught utterly off guard when the emasculated wilderness bares its teeth and bites back.

The summer following Wendy’s attack, a bear wandered onto Samatha’s property in the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains and killed a goat named Percy. Her neighbors asked her to shoot the animal. Devastated, she called Wendy and told her that she wanted her goats to live and for the bear to live, too. Coexistence with apex animals isn’t easy. After consulting with Wendy, Samantha built a new enclosure for her flock and started taking them in every night, precautions that reflected a new awareness of what it means to live with wilderness.

The world isn’t ours. So much of what happens is beyond our control. There’s comfort and beauty in acknowledging our smallness.

Wendy’s injuries have mostly healed, though her neck pain persists and she can’t lift her chin to gaze up at the sky. Her recovery left her homebound for months, and people came to her in surprising ways. An old high school friend from a rival basketball team held a shrimp dinner at her country gas station to raise money for Wendy’s medical bills. Wendy’s sister-in-law started a GoFundME page. A country church sent a check for $15. When she was well enough, Wendy returned that generosity by volunteering as a peer counselor at the hospital, meeting with other patients in recovery from traumatic injuries. “There’s the woman in Hanover who was attacked by the shark,” Wendy said, referencing an animal assault that had been in the news. “She lost an arm. I imagine she’s going to need a lot.”

Wendy says she was lucky on the day of the attack. The bear left. The phone call went through. The ambulance came. The helicopter rose. But when I listen to her, it’s not her luck that strikes me as much as her gratitude. Samantha insists Wendy was born this way—perpetually curious and optimistic and forgiving—but Wendy credits the bear with giving her this perspective. She says the attack and her subsequent recovery opened up something new in her, reminding her of those universal truths that most of us are too busy to acknowledge, much less believe: The world isn’t ours. So much of what happens is beyond our control. Though we might get hurt, there’s comfort and beauty in acknowledging our own smallness. “It makes [me] see the awe of nature,” Wendy told me. “It’s not all about you. You’re part of this whole big thing.”

This story originally appeared in Issue No. 1 of Southlands.