This story originally appeared in Issue No. 01 of Southlands. You can escape your screen and dive into a print version of the story by ordering a copy in our shop. And be sure to subscribe to receive the next two issues.

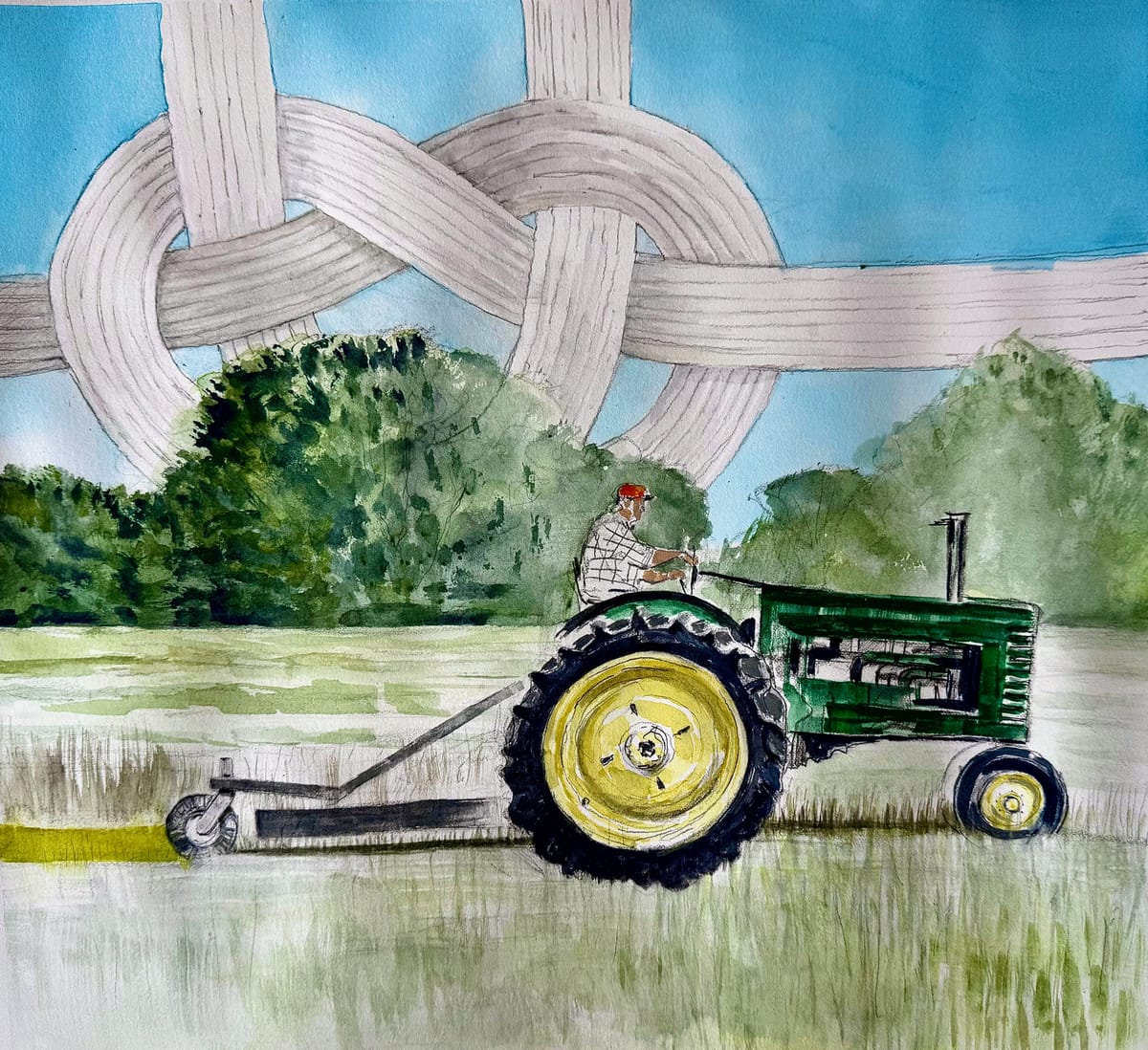

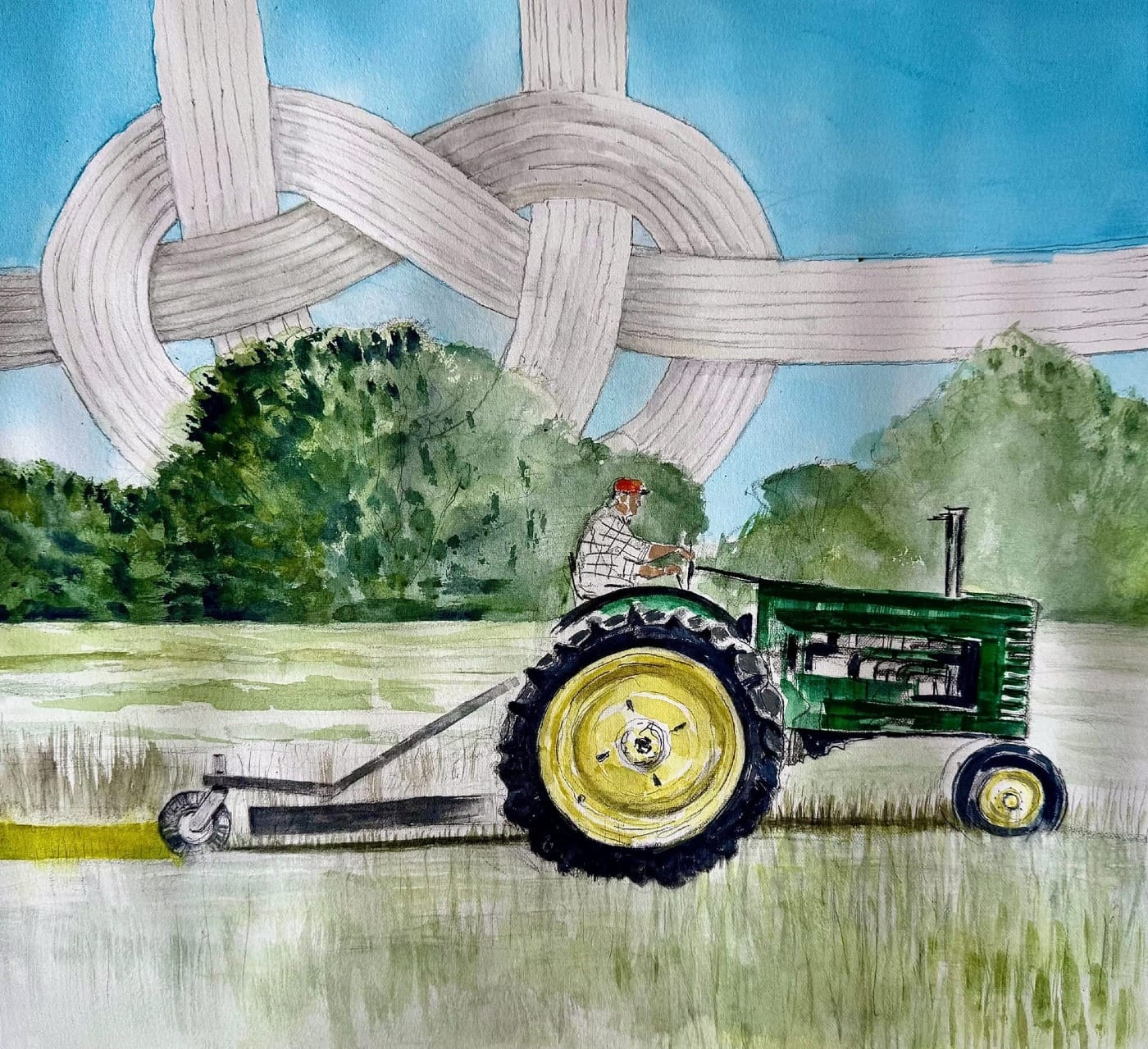

The morning of Grandma’s funeral, my uncle went out on the tractor to bushhog the weeds around the deer stand in the clearing. Stand Five was Grandma’s favorite place on “the farm,” which is what we called the 220 acres of land outside of Montgomery, Alabama, where Isabelle Hisako Tanaka spent the final years of her life. Stand Five was built in a small clearing, amid old oak trees draped with Spanish moss. Grandma loved to drive her off-road golf cart here to sit in the dappled sun and listen to the woods.

My father dug a perfect hole, round and deep, for her tree. We chose a persimmon. She loved that fruit, which has a special meaning in Japanese culture. Firebird orange and sweet, persimmons represent long life, and the trees live for many years. Our family would often receive a box of persimmons in the mail around Christmas, a gift from another Japanese family.

The afternoon thunderstorm came like clockwork, cooling the August air. After the rain, we drove our pickup trucks through the muddy fields. One of my cousins had cleared a path for us on the tractor. Our procession—respectful but not too solemn—took us across the creek, past the fish pond, through the shoulder-high grass where the deer pause to graze. We gathered in the clearing around Stand Five.

The pastor wore a shirt and tie over dress slacks tucked into mudding boots. A silver cross dangled from his belt, a Bible was tucked under his arm. He told us to be silent, to listen to why she loved this place. We stood in a circle, hearing the roar of cicadas, watching the daredevil flight of the dragonflies.

He kept the service short and sweet, like a fuyu persimmon. That’s how Grandma would have wanted it. Even toward the end, she would roll her eyes if our fussing got out of hand. Each one of us turned to the person on their right and whispered a lesson we’d learned from her.

I. Not From Around Here

I don’t remember Grandma ever baking us cookies, sending birthday cards, or making a single casserole. My white grandma, who lived in Kansas, made cream pies and let me play dress-up with her scarves and costume jewelry. My Japanese grandma did none of those things.

She was stoic and regal, the doctor’s wife, a lady from another era. She smelled like Oil of Olay, wore pearls, and spoke fluent Spanish. She moved with a lightness, like a dancer, floating through a realm where everything around her seemed denser. She was the only one who could call me “Kimberly” without making me cringe. She signed her letters, All my love, Grandma Hisako.

As an afternoon snack for us grandkids, she made tea and rice and wieners. O-chazuke is a Japanese peasant dish—hot green tea poured over stale, day-old rice to soften it. Eaten like a soup, it’s traditionally served with tsukemono (Japanese pickles) and maybe a small serving of fish. In Alabama, Grandma paired it with beni shōga (red pickled ginger) and Oscar Mayer wieners.

My cousin Matt and I joke that we come from a short line of Asian rednecks. Like me, he and his brothers are half Japanese.

The best years of my childhood were spent on an Alabama catfish pond the color of café au lait.

I reckon that makes us Yellownecks. In Hawaii, we’d be called hapa haole—half white. In Alabama, we’re just anomalies.

When I fill out documents that ask for racial background, I’ve always checked the box beside “Asian / Pacific Islander.” My cousin Matt always checks “white.” There isn’t really a box for us.

My great-grandparents were first-generation immigrants from Japan who lived and farmed across four western states. My great-grandmother—who some family members suggest was the illegitimate daughter of the emperor—became a legendary midwife in El Paso. My grandfather, a doctor, served as an Army field surgeon during World War II—Field Ribbon, five Bronze Stars—but, for reasons he never talked about, did not return to his family practice in Phoenix once he came home from Europe. I’ve always presumed that, like most Japanese-Americans, he’d found his home and belongings destroyed or “redistributed” to other Americans.

My grandparents researched towns to find a community that would treat Japanese-Americans with kindness. They fell in love with Santa Barbara, California, where grandpa became a pioneering physician, founding one hospital and serving as the attending physician at another. He was running a small family practice when I was born—the first of four grandkids, and the only girl. I took my first steps in the house next door.

Then, when I was five, my dad took a job in Fort Rucker, Alabama, the national headquarters of Army Aviation. He did human factors research that informed the design of first-generation helicopter flight simulators. We moved to Ozark, a small town twenty minutes from Dothan, the Peanut Capital of the World. My uncle, a doctor like his father, moved to Anniston a few years later for a job in emergency medicine.

The rest of the grandkids began to come along when I was ten: Matt and his brothers, Paul and Riley, were born and raised in Montgomery, Alabama. The three of them—the Tanaka boys—grew up hunting and fishing, driving pickup trucks with gun racks, bushhogging their land with a tractor. They played baseball. Matt, the catcher, went all the way to the Little League World Series. They grew into Southern gentlemen and married gorgeous white women whose homes look like pages from Southern Living.

She was stoic and regal, the doctor’s wife, a lady from another era. She smelled like Oil of Olay, wore pearls, and spoke fluent Spanish. She moved with a lightness, like a dancer, floating through a realm where everything around her seemed denser.

My upbringing was different. We kept on moving—back to Santa Barbara, then to Florida’s Gulf Coast, the Redneck Riviera. It was a bit of cultural whiplash. The rules constantly shifted as to whether I should or should not call my teachers “ma’am.” My friend group went from almost no Asian kids to a United Colors of Benetton ad—and back.

“Where are you from?”

I got (and still get) that a lot—in the South, and also out West. Embedded in the question is an implicit assumption: Ain’t from around here, are ya?

After Grandma’s funeral, I got to wondering: How did Isabelle Hisako Tanaka—the daughter of a legendary midwife in El Paso, the wife of a pioneering physician in Santa Barbara—come to spend her final days on a hunting preserve in the woods of Alabama?

How did our Japanese-American family become Southerners?

Are we? Am I?

II. The Catfish Pond

The best years of my childhood were spent on an Alabama catfish pond the color of café au lait.

We lived in the woods on the outskirts of Ozark. Down a steep hill, through the trees, were six catfish ponds where customers paid to fish. They used cane poles with no reels, which now seem kind of avant-garde, like redneck Tenkara rods. But instead of a fly on the end of the line, a hook was baited with chicken livers or nightcrawlers. Catfish aren’t picky like trout. I’m pretty sure I once saw someone catch one with Wonder bread squashed in a wad.

I don’t remember fishing at the pond, but I do recall feeding the fish. I think it involved using a coffee can to scoop dry pellets from a fifty-pound sack from the Feed & Seed. Those catfish whipped the pond into a froth. It was like Shark Week.

When it rained, the upper pond would overflow, and minnows would spill into the rutted tire tracks in the red clay road. My friend Shelley and I spent long sunburned afternoons bailing them out with a Solo cup. We thought we were saving the world.

Those were the days of free-range childhood, and my parents let me roam the woods alone. That’s how I learned to catch frogs, squeeze through a barbed-wire fence, and outrun the bull I encountered on the other side. I can still hear the dry leaves crunching under my running feet.

One summer day when I was nine, I was poking around puddles teeming with tiny frogs that had minutes ago been tadpoles. Going from puddle to puddle, cupping a handful of froglings against my shirt, I found myself desperately searching for grown-ups. Where there are grown-ups, there tend to be Mason jars. On the edge of the biggest pond, I found some adults gathering under a gazebo. They didn’t have a jar, but they gave me a Captain D’s bag. I didn’t even have to poke holes in it.

Noticing I had been gone for some time, my mother tracked me down. The adults were water skiing on the pond, which had a slalom course and a jump. Mom had grown up water skiing on the Colorado River. I’m not sure if it was her idea or theirs, but they offered to teach me to ski.

Unconsciously, I learned how to take up space and move through the world with the confidence of an average white boy.

I remember the frogs more clearly than I remember the first time I got up on water skis. But soon I was running the slalom course, carving tiny arcs of spray around buoys the size of my head. I entered a tournament. Then another. And another. I competed in State. Regionals. Nationals. I learned how to tuck and roll. I learned tricks that required falling hundreds of times before the first success. One day, I’d choose my college from the ones with a water-ski team. (Roll Tide!)

The other young skiers were Southern boys, all a few years older than me. They came to feel like brothers. We roughhoused and wrestled and had seaweed fights, wadding swaths of milfoil around balls of wet clay. It was the golden age of WWF, and the boys were into Hulk Hogan and Andre the Giant. I got slam-dunked a lot in the pond.

Let me be clear: This was not abuse. It was Type Two fun—and useful. I learned to hold my breath and fight back. I had fingernails. And a pinkie-finger ninja move that could bring a boy to his knees. Unconsciously, I learned how to take up space and move through the world with the confidence of an average white boy.

III. The Deer Stand

My mother would have made a great tomboy, had her mother allowed it. Instead of climbing trees as a kid, she was forced to play the violin. So she turned me loose in the Alabama woods. When I wanted to be Peter Pan for Halloween, she sewed me a green felt tunic and didn’t even mention Tinkerbell.

My white father, a scientist and a man’s man from Kansas, aided and abetted. We’d pick cattails from the edge of the pond and light them on fire as torches. He taught me how to drive a go-cart and turned our circular driveway into a NASCAR track. He built an epic rope swing from the tallest tree on the hill, and when you swung out, the Earth fell away and it felt like you were flying. My childhood friends, now middle-aged, still talk about that rope swing.

Later, I drove a four-wheeler through the woods and past the ponds to tap dance lessons at my teacher’s house. I got cut during cheerleading tryouts, but I was part of a tap dancing trio that performed during intermission at the Little Miss Peanut Pageant.

One day, dad said he was going to build me a tree house. He nailed two-by-fours to the trunk of a hardwood so I could climb to a good-sized sitting branch. There was no house. No walls. No roof. Not even a plywood platform to sit on. Years later, I realized that this sitting branch was not, in fact, a tree house.

It was a tree stand.

I’m not sure why my father got into deer hunting. He spoke of hunting pheasants and quail in Kansas. Deer hunting was something men did in Alabama.

My father was one of the best saltwater fishermen I know. He could outwork men half his age. But he wasn’t much of a hunter. He would pull on camouflage coveralls and anoint himself with deer pee, then climb up into my “tree house.” He spent many cold mornings sitting on that branch, and not one deer ever wandered by.

Then, one morning before school, I was spooning Cheerios into my mouth and staring out the kitchen window when I saw an unfamiliar creature meander toward the house, stopping to nibble at the pile of dry corn we’d poured on the ground for the squirrels.

“Mom!” I said. “Look at that funny long-legged dog!”

My father was getting dressed for work. Wearing nothing but his underpants, he grabbed his rifle, rushed onto the porch, and took aim. As the shot rang out, I was already sobbing in my mother’s arms, face buried in her nightgown. It was right around the time Bambi was re-released for its fortieth anniversary.

“I shot a deer in my underpants,” he later told his colleagues.

“What was a deer doing in your underpants?” they joked.

It was the only deer my dad ever shot.

IV. The Deer

How the farm came into our family is still a bit of a mystery to me.

Someone recalls Grandma getting a bee in her bonnet about buying her boys some land. Others say the notion started with my uncle Paul. He wasn’t into hunting himself, but he was a mad-scientist type and a tinkerer, and the land would give him a place for his experiments and projects. And it would give his sons a place to hunt.

My cousin Matt, the middle child, was thirteen when he got into bowhunting. He went with friends and joined a local hunting club in Montgomery. Alabama has 1.3 million acres of public lands open to hunting, but a lot of folks hunt on private lands, many of them owned by clubs managed for that purpose.

One day Matt and his friends were hunting with the club on private lands. Someone shot a nine-point buck, which took off into the woods. Together, they followed the blood trail, tracking the wounded deer.

The blood trail led to a tract of private land for sale.

Years later, I realized that this sitting branch was not, in fact, a tree house. It was a tree stand.

It was a patchwork of open meadows and pastureland with stands of loblolly pines and palmettos, wild oaks dripping with Spanish moss. The pastures had been used for grazing but were now wildlife openings that might attract deer. A creek ran through the property and overflowed once or twice a year into lowlands that became wetlands.

“Dad called that part ‘The Mekong,’” Matt told me recently. “It was loaded with wildlife. Turkeys, snakes, you name it.”

The only structure on the property was a dilapidated house that slouched so severely it looked like it had never known a right angle. The windows were busted, the wood porch sagged, and the roof was caving in.

It was perfect.

Uncle Paul looked at the derelict house and saw a storage shed. In the land he envisioned a hunting preserve, a landscape where his boys could develop skills and grow themselves into men. A piece of land where they might bring their future kids. He bought it.

Next to the falling-down house he put a brand-new storage shed. He built bunk beds, added air conditioning and a patio. After splitting up with his wife, he had been sharing a cramped Montgomery apartment with his brother, Peter. This became their weekend basecamp for hunting and man-glamping. Paper plates and plastic utensils meant no dishes to wash. They could leave clothes on the floor and weapons on the dinner table and no one would fuss.

I caught only occasional glimpses of how each of my cousins grew into a particular kind of hunter. Matt loved bowhunting for white-tailed deer. He was still in middle school when I watched, impressed with his skill and composure, as he dismantled one with a buck knife. His older brother, Paul, Jr., fell in love with wood ducks. The youngest brother, Riley, favored wild turkeys.

When it wasn’t hunting season, Uncle Paul took the boys on trips around the world. Costa Rica. Alaska. Tahiti. He wanted his boys to see that there was a world outside Alabama. Most of the time, the accommodations were as rustic as the hunting camp.

At the time, from afar, I was envious that they got to travel the world. I later learned how hard he made them work. Uncle Paul gave them dirt bikes, rifles, rods, and fishing trips. But they had to bait their own hooks and clean their own fish. At home, he made them fix windows, bushhog the fields, disk the land, dig holes, plant trees.

“Everything he did was very intentional,” my cousin Paul told me. “He found good ways to prepare us for life.”

Under his guidance, my cousins shaped the farm into a landscape that would nurture all kinds of wildlife. They planted the meadows and former cattle pastures with velvety swaths of alfalfa, a high-protein food source that nurtures fawns and antlers. They framed the alfalfa with hallways of honeysuckle vines sprawling over mounds of chicken wire. That would offer concealment, a sense of protection.

“Dad called it Honeysuckle Lane on Deer Alley,” Matt says.

The land was already riddled with wild persimmon trees, those symbols of luck and longevity. “I’ve never seen so many wild persimmons,” Matt says. I didn’t even know they grew wild in Alabama. They planted more, knowing the naturally sweet “tree marmalade” would attract and nourish wildlife.

The land was also riddled with spiders.

V. The Spider

As Uncle Paul and his boys transformed the land, Uncle Peter designed their dream house. A stone hearth for wood fires in a great room with windows that overlooked the fields. The great room flowed into a large kitchen with an eight-foot island. Peter loved to cook.

One day he was poking around a wood pile by the dilapidated house when he was bit by a spider. A brown recluse.

The spider bite grew a bull’s-eye, then turned into a nasty wound. Necrosis. When Peter fell ill with fever and aches, he thought he had the flu. Paul, the doctor, diagnosed something more insidious. Bacteria from the infected wound had traveled through Peter’s bloodstream and landed on his heart valve.

Peter was rushed into open-heart surgery, where they replaced his infected valve with a healthy one from a pig. Soon, he was up and about. We were grateful for Paul’s diagnosis and the miracle of medicine.

Then the infection came back.

Their sentences warped, like words spoken underwater. But their solemn faces spoke chapters. Grandma slumped against my mother and cried awful silent tears. She would never be the same.

My mother and I hugged Peter before they wheeled him into the operating room. My husband and I had just bought our first house across town, in Birmingham. Instead of sitting in the waiting room, we took Grandma and Mom to see it. We were admiring the backyard garden when we got an urgent call from the hospital.

The surgeon and two other doctors—or maybe nurses, it’s all a blur—sat before us in a triangle, like migrating birds in an echelon. Their sentences warped, like words spoken underwater. But their solemn faces spoke chapters. Peter had died on the operating table.

His skin was still warm and soft when we held his hand and said goodbye. Grandma slumped against my mother and cried awful silent tears. She would never be the same.

In the days that followed, we walked through the near-finished house on the farm. Sunlight streamed through the picture windows. My mother sobbed quietly, hand over her mouth as if to hold in the screams. I stood in the vaulted living room and walked through the rooms of Peter’s dream.

My aunt flew out from California and three surviving siblings gathered for what would turn out to be the very last time. We planted a memorial tree—a persimmon. Peter’s dream house shimmered across the fields as we set it into the ground to take root.

VI. The House

Despite the tragedy, the house was there. It made sense for Uncle Paul and Grandma to live in it.

Grandma kept her room tidy, with a statue of the Virgin Mary on her nightstand and a rosary draped over it. She was always cooking or cleaning, but the house remained a spectacular two-story man-cave. Labrador retrievers dashed through the house. Hunting bows, rifles, knives, and tools lay scattered on every flat surface. It was the kind of place where you might find an injured hawk in the bedroom or a live snake in a Tupperware container in the kitchen.

My favorite memory of the house was the one Thanksgiving we all spent together there after she died. They didn’t have a dining room table, so we gathered around a card table and sat in folding chairs. Someone bought autumn-themed paper plates and a tablecloth. We deep-fried a turkey and dished cranberry sauce out of the can with a plastic spoon.

We were fully grown now, and my cousins offered to teach me how to shoot a hunting bow. Having never done such a thing, I drew back the bowstring and, without an arrow, released it. That’s how I learned that dry-firing is a good way to ruin a compound bow. I also learned—the most painful way—to keep my double-jointed elbow out of the way of the bow string.

The string scraped the tender inside of my elbow at somewhere around three hundred feet per second. The only worse pain I’ve known was childbirth. A purple welt the size of an eggplant immediately appeared. My eyes began to water, and in my blurring peripheral vision I saw my boy-cousins wince.

She never complained, and she floated through the chaos, an island of calm, elegant even in sweatpants.

Being the oldest cousin and the only girl, I knew I could not cry. I breathed deeply through the knee-buckling pain, asked for an arrow, took aim, and hit the target. Then I lied about having to pee and excused myself to the bathroom. Out of sight and earshot, I braced myself against the commode and doubled over in dry heaves.

Grandma’s existence in this mandom was a curiosity to me. She never complained, and she floated through the chaos, an island of calm, elegant even in sweatpants. It was so different from the home she curated in Santa Barbara, decorated with Japanese painted screens, paper fans, and lacquer chests.

In Santa Barbara, she drove a Mercedes that Uncle Paul bought her with his doctor’s salary. On the farm, she drove a diesel off-road golf cart. Or maybe it was a Mule. Maybe the woods around Stand Five offered her some peace and quiet, a place to sit and think. Or remember.

After my grandfather’s death, my mom had invited Grandma to live with her and my father in their meticulously clean house in Florida. But Grandma had always declined.

Mom told me that Grandma had always preferred the company of men. Her two brothers treated her like a princess. At nineteen, she won first prize in the Southwest Sun Carnival—a beauty pageant, I presume—and had ridden on a “Springtime in Kyoto” parade float wearing a kimono and a crown of flowers. Maybe there was a little bit of Japanese Scarlett O’Hara in her.

Maybe she liked being different.

The summer after Peter died, Grandma’s health started to fail. She was 88. I think she might have lived longer if she hadn’t lost a child. He was her baby, and he doted on her.

In the hospital, Grandma showed legendary Japanese stoicism in facing all the needles. She never flinched, and kept her sense of humor.

“We’re going to have to stick you a little,” the nurse said. “Is that okay?”

“No,” Grandma said weakly, mustering a smile.

Watching her get a blood transfusion, studying the maze of filters and tubes that looped and merged into her arm, I thought how odd it was to see a stranger’s blood trickle into my grandmother’s body. I begged her to eat, to regain some strength.

“You’d better listen to Kim,” my mom said. “She has a mean punch.”

Grandma didn’t miss a beat: “So do I!”

She wanted to go home. So we brought her home, which now meant the farm.

VII. The Family

She napped in a giant La-Z-Boy recliner that dwarfed her eighty-pound body. We carried her to the bathroom, dabbed her face with a moistened towel, held cups of 7UP that she could sip through a bendy-straw.

One Monday afternoon, she lay propped in the chair, surrounded by family. Paul, the doctor, had given her some sort of medicine to keep her hanging on until everyone arrived. She was Catholic, and we might ought to have had a priest on hand to administer last rites. But she hadn’t been to Mass in decades, and priests can be hard to come by in rural Alabama. The pastor would do in this pinch, and I figured not even a Catholic God would lock her out for our transgressions.

We opened the door and swiveled her chair to face the open doorway. Outside, in the heat of an Alabama August, cicadas sang from thickets of grass and dragonflies filled the air. The pastor knelt down beside us.

“What I see tells me a lot,” the pastor said, looking us in the eye. All eleven of us—kids and grandkids, spouses, and friends. “Ninety percent of the people I visit die alone.”

Mom told me that Grandma always preferred the company of men. Maybe she liked being different.

We each laid a hand upon Grandma, as if by touching her we might carry her home. She grasped a hand on either side and gripped it with a tremulous strength astounding for one unable to stand or hold up her head. The day before, she’d lost her strength. She lacked the strength to sip water.

Her time was near. We could feel it. We could see it. In her ragged breath, her distant eyes. Those eyes followed something outside the open door. We looked out and saw green fields and silver clouds pregnant with rain. She seemed to see something else. Her lips moved, but no words came. From time to time, tiny arms reached out and cradled someone we could not see.

“Who are you hugging, Mom?” my mother whispered.

We studied her face, watched the emotions dance across it. Her open mouth curved into shapes of horror, surprise, then something like joy. Her cheekbones rose high above her sunken cheeks. Her eyebrows rose and furrowed. Her eyelids opened and closed. From time to time her body would tense, and she’d grip our hands with a strength she couldn’t possibly have.

I had the very strangest thought just then: If Norman Rockwell had painted death, it would have looked like us.

Time turned to honey as we studied her face, watched the rise and fall of her chest, waiting for her last breath. From her throat came a guttural noise. The death rattle, I thought.

She was snoring.

Later that afternoon, she regained lucidity. I played Clair de Lune on the stereo. She was a beautiful pianist, and as a child, I loved listening to her play the song in her Santa Barbara living room. I would lie on the carpet under the grand piano, hearing the click of the keys, watching her tiny feet working the pedals. Now, as she heard the first notes, her eyes widened and eyebrows rose. Uncle Paul saw her face and said, “She likes that.” He asked me to play it again.

In the hours and days that followed, people came and went. My uncle’s current girlfriend and former wife—both nurses—worked together (mostly). One would rig the IV in Grandma’s arm, then quietly leave her to rest. As soon as she left the room, the other would secretly “fix” it.

Refusing food and water, Grandma didn’t weigh enough to keep the recliner reclined. My uncle, ever resourceful, filled a Clorox bottle with water and tied it to the back of the chair to keep it in position.

Grandma’s lungs filled with fluid, and she started to asphyxiate. Drowning in your own fluids is a horrible way to die. There wasn’t time to get her to the hospital in town. Uncle Paul intubated her lungs with the speed and skill of an ER physician. Then he duct-taped the other end of the catheter to a Shop-Vac, which bought a little more time.

In her final hours, it was just Uncle Paul, my mother, and me. Grandma’s eyes were glazed over, and they no longer followed us across the room. With an eye dropper, we dripped morphine into her parted lips. Her breaths grew smaller and farther apart. And then, at last, they stopped.

VIII. The Lesson

On that steamy August afternoon, we gathered to say goodbye in a way that I feel certain has never occurred, before or since, in Alabama. We’ve always lived a bit outside of social conventions, and it felt beautiful and true to forego a traditional service in some stuffy funeral home.

As the men went about digging and planting the tree, I rigged my iPod to play through the speakers of my silver Toyota Tacoma. Since Grandma was Catholic, I wanted to play Ave Maria. And, of course, Debussy’s Clair de Lune.

Now, as we stood in a soggy field in Alabama on that August afternoon, the songs she loved to play poured out of my pickup truck’s open doors. In the haunting beauty of those lilting notes, soaring over a chorus of cicadas, I could almost hear her voice.

Earlier that morning, my mother and I had folded dozens of origami cranes, a symbol of good fortune and longevity. When someone is sick, it’s customary for friends and family to fold one thousand paper cranes in a gesture of hope and healing. When I was little, while we waited for our food at a restaurant, my mother would distract me by folding the paper place mat into a paper balloon or a crane. In first grade in Alabama, I taught my classmates.

I had the very strangest thought just then: If Norman Rockwell had painted death, it would have looked like us.

The morning of Grandma’s funeral, we didn’t have time to fold one thousand. We made enough for each person, for a ceremony we invented on the spot. We didn’t have origami paper, so we made them out of printer stock, with a loop of fishing line for hanging, like an ornament.

While the music played through my truck’s speakers, we passed them out. One by one, each of us hung a crane on a bare branch of a persimmon tree and said goodbye to Isabelle Hisako Tanaka.

Each of us whispered a lesson she taught us. I can’t remember what I whispered, but I’ve been thinking a lot about what parts of her live on in me.

I inherited her Japanese middle name. Hisako means “eternal child.”

As she did, I try to live up to it, but in my own way. Not through Oil of Olay. But rather by keeping the girl inside alive through the joy of childhood play. I love the words of George Bernard Shaw: We don’t stop playing because we get old. We get old because we stop playing.

I’m not a princess like she was. But like her, I am comfortable being different. The only girl water-skiing at the catfish pond. The only middle-aged mom at the bike park, riding dirt jumps with teenage boys.

I still can’t decide if I’m a Southerner, or if she was, but I know I’ve found an identity in being an anomaly. Wherever I am, I am “not from around here.” And yet I feel at home everywhere. Being mixed-race, I can pass for almost anything, and people tend to see in me the bits we have in common.

My mother never visited Japan, though we still have relatives there. Before I became a mother, I decided I ought to visit them.

Sawako, a fifty-year-old relative who took me there, had been a twenty-year-old girl when my grandmother had hosted her in Santa Barbara on her first journey outside of Japan. I was five then, and remembered her as the first “real” Japanese person I’d ever met. To celebrate the New Year, she and her family would send us persimmons.

Sawako took me to a cemetery in Mera, a tiny fishing village where my great-grandmother was born. Big Grandma died in El Paso, Texas, but she wanted her ashes, along with her husband’s, to return to Japan. A distant relative—the great-granddaughter of her sister—taught me the Japanese custom of honoring them by pouring water on their gravestone.

As Sawako and I checked into a ryokan—a small inn with a Japanese hot spring called an onsen—I heard a familiar song. It wasn’t the koto-and-flute music I expected in a Japanese spa. It was a song that felt like a whisper of my grandmother from the past.

The song was Clair de Lune.

As I write this, it has been twenty years since her funeral. Her tree is hard to distinguish from all the wild persimmon trees that have sprung up around it.

Somehow, we never got around to spreading Grandma’s ashes. My cousin Matt told me to ask my mom, now 84 and fading, where she thinks Grandma would want us to scatter them. My mom didn’t pause before answering.

“The farm.”

This story originally appeared in Issue No. 1 of Southlands.